The USS Skipjack and the Toilet Paper Incident

From “More Sub Tales”

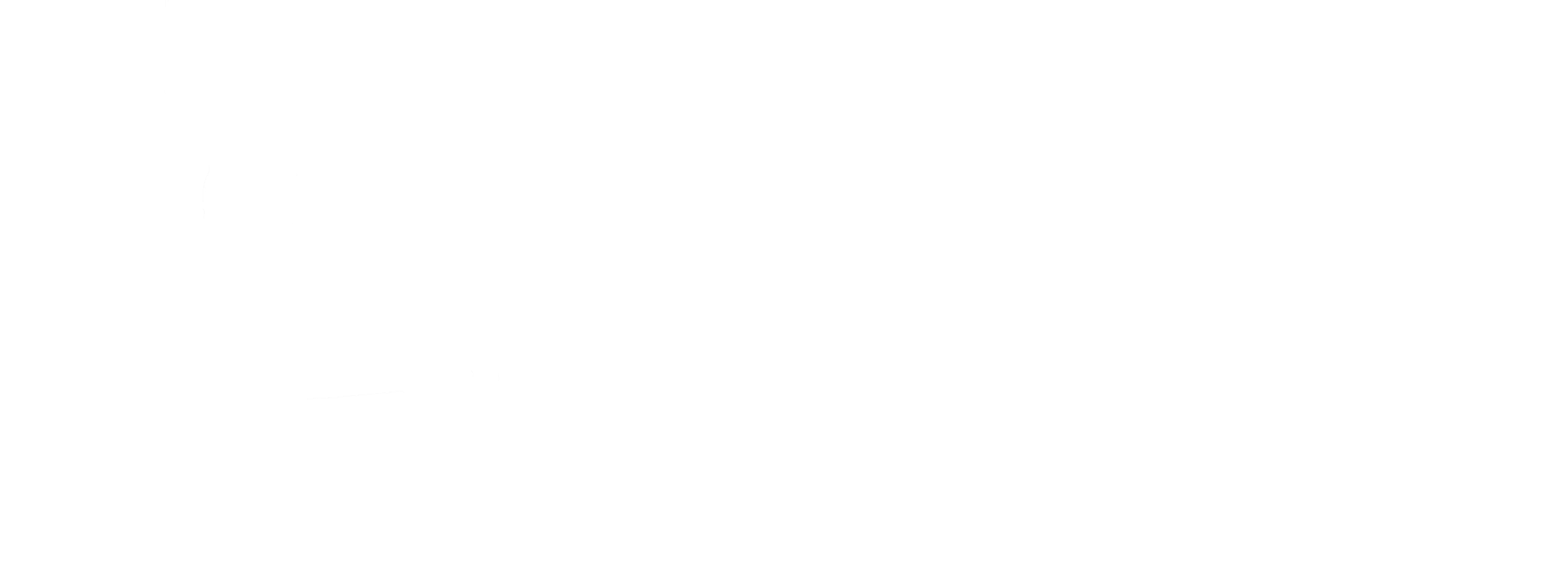

As a vivid illustration of how the US Submarine Force took on the mantle of “first responders” in the prosecution of the war against Japan, less than 48 hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Skipjack had already departed Manila to begin her first war patrol under the command of LCDR Charles Freeman. That patrol, and the one that followed, were unsuccessful in sinking any enemy ships. Before the third war patrol began in April 1942, a change of command brought in LCDR James Wiggins Coe to lead the Skipjack. Known by all as simply “Red”, Coe brought a more aggressive approach that netted immediate results. On the third patrol, four Japanese ships were sunk, including a Japanese cargo ship where Coe’s audacity helped to change submarine tactics for the remainder of the war.

On 06 May 1942, Coe pioneering the so-called “down the throat” shot—essentially the submarine version of playing chicken with the enemy. Approaching the freighter bow-to-bow, the usual playbook called for Coe to order an immediate dive—in the hopes of finding temporary refuge beneath the enemy ship’s hull as it passed overhead. Instead, at a distance of fewer than 1,000 yards, Coe chose to reel off a salvo of three torpedoes aimed straight for the ship’s approaching bow. The freighter sank, and the strategy manual was rewritten. Other boats would choose to utilize the same technique against the Japanese destroyers hell-bent on depth-charging them into oblivion.

While Red Coe won acclaim for his prowess at sea as a submarine commander, he is probably best remembered today for his letter to the supply officer at Mare Island in June 1942. Written between the third and fourth war patrols of the Skipjack, the missive drips with sarcasm as Coe requests assistance in solving a dilemma that was affecting both sanitary conditions and morale aboard his boat: a toilet paper shortage.

Coe’s supply officer had requested 150 rolls of toilet paper from the sub tender USS Holland (AS-32) the previous summer, but the order was never fulfilled. Instead, almost a year later, Coe received a canceled invoice from Mare Island for the 150 rolls stamped with the words “Canceled—cannot identify.” This blunder inspired the following letter from Coe, considered one of the most memorable naval communications of all time.

USS SKIPJACK 11 June 1942

From: Commanding Officer To: Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, California Subject: Toilet Paper Enclosure: (1) Copy of canceled invoice; (2) Sample of material requested. 1. This vessel submitted a requisition for 150 rolls of toilet paper on July 30, 1941, to USS Holland. The material was ordered by Holland from the Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, for delivery to USS Skipjack. 2. The Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island, on November 26, 1941, cancelled Mare Island Invoice No. 272836 with the stamped notation “Canceled—cannot identify.” This canceled invoice was received by Skipjack on June 10, 1942. 3. During the 11 ¾ months elapsing from the time of ordering the toilet paper and the present date, the Skipjack personnel, despite their best efforts to await delivery of subject material, have been unable to wait on numerous occasions, and the situation is now quite acute, especially during depth charge attack by the “back-stabbers.” 4. Enclosure (2) is a sample of the desired material provided for the information of the Supply Officer, Navy Yard, Mare Island. The Commanding Officer, USS Skipjack cannot help but wonder what is being used in Mare Island in place of this unidentifiable material, once well known to this command. 5. Skipjack personnel during this period have become accustomed to use of “ersatz,” i.e., the vast amount of incoming non-essential paperwork, and in so doing feel that the wish of the Bureau of Ships for the reduction of paperwork is being complied with, thus effectively killing two birds with one stone. 6. It is believed by this command that the stamped notation “cannot identify” was possible error, and that this is simply a case of shortage of strategic war material, the Skipjack probably being low on the priority list. 7. In order to cooperate in our war effort at a small local sacrifice, the Skipjack desires no further action be taken until the end of the current war, which has created a situation aptly described as “war is hell.” J.W. Coe Needless to say, Coe’s letter achieved its goal—and then some. When the Skipjack returned from her fourth war patrol to Fremantle, Australia, on 04 September 1942, the pier was stacked high with boxes of toilet paper arranged in seven-foot-tall pyramids. A band greeted the submarine wearing toilet paper ties, and toilet paper streamers adorned the dock light posts. Two sailors held the free ends of two rolls of toilet paper mounted on a long wooden dowel while two other sailors ran to the other side of the pier carrying the dowel, thus completely unspooling both rolls like streamers.

The Baseball Game at the North Pole – Hit a Ball into Right Field, and You Hit it into Tomorrow

From “Sub Tales”

The sister ship of the Seadragon, USS Skate (SSN-578), had been the first submarine to surface at the North Pole on 11 August 1958; only eight days earlier, on 03 August 1958, the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) had completed the first submerged transit of the North Pole! A third US submarine, USS Sargo (SSN-583), had also visited the North Pole in February 1960, so Seadragon would be the fourth submarine to make the trip and the third to surface in Santa’s backyard.

During her journey, Seadragon examined and photographed the underbellies of many giant icebergs, many of which were far larger than scientists had once believed. She carried the world’s original underwater solid-state video camera to record the eerie ecosystem for the very first time. For example, earlier in the trip during the traversal of ice-choked Baffin Bay, she dove below an iceberg that extended more than 300 feet below the surface, allowing scientists aboard to study it closely with advanced television and sonar equipment.

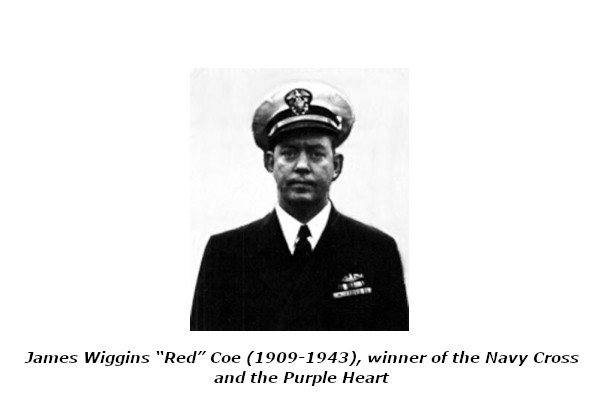

The mission of the Seadragon was clearly memorable for several important scientific and logistic reasons, but let’s put the serious stuff aside for a bit and talk up the story of the famous softball game that transpired once the Seadragon surfaced at a polynya only a tenth of a mile from the North Pole on 25 August 1960.

For a few apprehensive minutes just before the Seadragon arrived at “Latitude 90 North”, the Navy lost radio contact with the boat. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when her skipper, CDR George P. Steele, reported in loud and clear upon surfacing at Santa’s home base: “The temperature at the surface on the North Pole is 28 ° F. The weather is fine and the sky is clear.” In no time after surfacing, plans were enacted to transfer men by life rafts over to a neighboring large ice floe about 15 feet away, where the actual geographic top of the world was located. Once safely on the floe, which was flat, featureless, and covered by ice and snow, the crew walked out and marked the key positions of a standard baseball diamond. The local time was close to midnight.

Two teams of nine players each were chosen to participate—officers and CPOs versus enlisted crew. Playing conditions were ideal: even though it was late at night, the sun was still shining brightly albeit low in the sky, and there was little to no wind. At the North Pole—indeed, anywhere above the Arctic Circle—the sun never sets during the six months between the spring and fall equinoxes. Before the guys began playing (yes, they had brought bats, gloves, and a generous supply of softballs), they contemplated the unique setting of their game. There were so many ways to dissect the geographic implications of the playing field!

All lines of longitude converge at the North Pole, including the Prime Meridian (0°) and the International Date Line (180° east or west). As most people know, the Prime Meridian passes through Greenwich, England—the reference point for Greenwich Mean Time. It is also common knowledge that you cross the International Date Line (IDL) moving from west to east, you subtract a day, whereas a day is added when you move from east to west across it. The baseball diamond was laid out with some attention to these parameters. First, the pitcher’s mound was placed directly at the location of the best estimate of the true North Pole. The home plate was then set at the Prime Meridian, and second base was placed at the IDL. (See the diagram at the end of the chapter to help you visualize the diamond layout.)

Such arrangements created some endlessly amusing yet true ways to describe the competition. Let’s hear it in the words of someone who was there—Officer Alfred McLauren, as he wrote in his excellent (and highly recommended) book, Silent and Unseen: On Patrol in Three Cold War Attack Submarines:

If a lucky batter on either side hit a home run, he could circumnavigate the world and pass through 24 time zones as he circled the bases on the way to home plate. If he hit the ball to right field, he would be hitting it across the IDL into tomorrow. If the right fielder caught it as a fly ball, he caught it the next day…However, if (the batter) hit a line drive into right field and the ball was successfully fielded and thrown to either second or third base, it would have been thrown back into the day of play, or yesterday. A ball hit to left field would remain within the same day…Double and triple plays could conceivably take several days to complete!

CDR Steele quipped that the men participating in the game had to be extremely slow baserunners because, after hitting a ball into play, any batter couldn’t reach first base until twelve hours later. In truth, it was difficult to run: the footing was precarious, and the players were braced against the cold wind by 15-25 pounds of clothing. In further comments to the press several weeks later, Steele also implied, tongue-in-cheek, that some of the most powerful baseball hitters were among his crew, since “up here, you can hit a baseball from one side of the world to the other.” Steele had also confidently predicted that the “old guys” (officers and CPOs) would “thoroughly trounce” the younger enlisted men. However, he had to eat his words, as the final score of the contest was 13-10, with the enlisted men coming out on top. (Steele concluded that “the youth and enthusiasm” of the crewmen trumped the “mature judgment and experience” of the submarine officers and CPOs.)

Around the World Underwater – with the Author of “Run Silent – Run Deep” as the Skipper – Ned Beach

From “More Sub Tales”

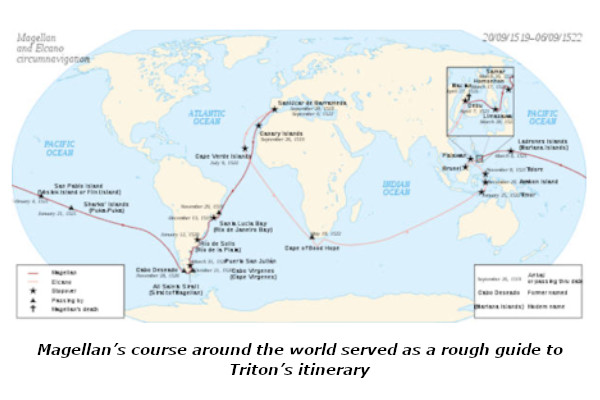

The mission was dubbed Operation Sandblast—a tip of the cap to the skipper’s last name. The goal of the mission: to completely circumnavigate the world’s oceans, entirely submerged, by following the path taken by the first group of explorers to achieve this feat: Ferdinand Magellan’s crew between 1519-1522. CO Beach and a few select officers of the Triton were first apprised at the Pentagon of Operation Sandblast on 04 February 1960; the remaining officers were informed the following day. Enlisted personnel were kept in the dark about the secretive plans for the time being.

One of the only inklings that the Carl and the other enlisted crew members had that something unusual was in the air was a directive received from the Navy shortly before departure to file their income taxes early and make sure their bills were paid up through May. The enlisted men were probably also intrigued by the sheer amount of food shoved into every available space. But the actual news that they would be out at sea for more than two months—submerged the entire way—had to come as something of a shock and a thrill at the same time. Their voyage would be truly historic.

Shortly before departure on what was billed as a routine shakedown cruise out of NLON, the supply officer on the Triton had his hands full. More than 75,000 pounds of food were stuffed inside—including nearly three-fourths of a ton of coffee. Carl wondered why there were so more stores crammed into every nook and cranny for just another short sea trial; plus, the regular crew was supplemented with a photographer from National Geographic magazine, and several civilian scientists, engineers, and even a psychologist also came aboard the morning of 16 February 1960.

It wasn’t until the following morning when CO Beach finally spilled the beans. As Carl recalled, the skipper got on the 1MC—the ship-wide communication channel—and announced, “Gentlemen, we are not going back to New London just yet. We are starting an around-the-world cruise, and we will do it all underwater without surfacing one time.” As the startling news began to sink in, the Triton set course for St. Peter and Paul Rocks in the mid-Atlantic Ocean. These Brazilian islands had been chosen as the “starting point” for the circumnavigation cruise because Magellan’s itinerary for his voyage (which he did not survive, as we will see) had taken him past this archipelago. Magellan’s crew needed three years to complete the trip; the Triton would require less than three months.

Carl Hall was a bachelor at the time, and although he doesn’t recall exactly where he was on the boat when the commander made the announcement, he does clearly remember the agonizing looks on the faces of his married shipmates, whose wives would be expecting them to return in a matter of days, not months. There is a famous picture of CO Beach making the startling announcement in Control; the facial expression of the enlisted man at the Ballast Control Panel to Beach’s left is priceless: “WTF?”

Carl points out that although the public reason given for the lengthy trip was to honor Magellan’s achievement, the real reason that the Navy green-lighted the mission was to show the USSR that the US had the capability to go anywhere, anytime, with its new fleet of nuclear submarines. It should be noted that the Navy remained tight-lipped about any details of the trip while it was underway; there would be no daily updates on the progress of the Triton in the local papers. Only when the mission had been fully and safely completed would the big news be shared with the American people.

As a QM—the enlisted man responsible for helping the OOD to keep the boat’s current position always updated on a nautical chart—Carl had picked up on another clue that something was afoot with this trip, apart from the cryptic letter instructing sailors to prepay their taxes and monthly bills. He noticed that the boat was carrying a lot more maps and sea charts than usual. Also, since the officers had been told about the nature of the trip more than 10 days before departure, some scuttlebutt had traveled around the base about some kind of “big news” forthcoming. During the brief period between getting the word about the extraordinary trip and shoving off from NLON, CO Beach spent many hours in private thoroughly studying the many surface maps and charts that would be needed to complete the trip.

Carl recalled that the twin nuclear reactors—installed such that either one alone could provide adequate propulsion—stayed online simultaneously for most if not all of the trip. As a result, virtually the entire trip was made at a very deep depth and a high rate of speed. Although the official record indicates an average speed of 18 knots (about 21 mph), Carl said that the actual speed was a good bit higher. The main concern for CO Beach, the OOD, and QM was the potential of ramming into an uncharted mountain rising from the ocean floor. Given the sheer length of the trip—more than 26,000 miles for the circumnavigation part, plus another 10,000 miles for legs to and from NLON—the likelihood of traversing a part of the ocean with poor or outdated maps was reasonably high. Fortunately, no such collisions occurred, and the ability to maintain a speed in excess of 20 knots nonstop for two months is astonishing, even by today’s standards.

That is not to say that there weren’t any close calls. Since many ocean peaks had not been discovered or charted at that time, the boat broke typical Navy protocol for the long voyage by using sonar in active mode, meaning it continuously “pinged” a signal out into the ocean to look for a sudden and unexpected return off an underwater mountain. They encountered one off the coast of South America near Cape Horn. The Triton cleared the summit by only 100 feet over the previously unknown mountain—within a whisker in oceanographic terms. After that, it was clear why there were so many extra civilian scientists on board—one of their objectives was to man special equipment to avoid such a calamity.

Many related pictures not shown here.

Stories by Jerry Topil

From “The Silent Service Remembers – Vol I”

Full-on-Four Dive

We were doing daily ops out of Charleston. This was early in my time aboard the Trumpetfish, so I was a mess-cooking nub in the galley. As such, I was only a spectator to what happened, but it was one of the scariest moments of my time aboard submarines.

Our CO was in Control qualifying Ensign Smith as a Diving Officer of the Watch (DOOW). This dive was going to be what we called a “full on four” dive; all four engines at full speed! When the order to dive the boat was given by the DOOW, back in Maneuvering the bell “Full on Four” was answered. From the bridge, Ensign Smith ordered a 15-degree down angle with a depth of 200 feet. In moments we were descending at 15 degrees at a speed of about 19 knots. We passed 200 feet on the fathometer.

Our test depth was around 400 feet. Before Ensign Smith had made it from the bridge to the Control Room, our down angle was increasingly rapidly. We were heading down at an angle of up to 40 degrees and soon passed our test depth of 400 feet. I remember trying to catch all of the stuff falling out of the lockers as our bow was turned sharply downward. The boat was shuddering, shaking, and groaning loudly. I would be lying if I said it wasn’t frightening.

Fortunately, three enlisted men acted promptly without orders to prevent a catastrophe. The quick-thinking EOW (Electrician of the Watch) in Maneuvering, Sal Farrera, threw the knife switches to All Back Emergency when he realized we were in trouble. In Control, the AOW (Auxiliaryman of the Watch) stationed at the air manifold opened the valves to blow HP (high pressure) air into the ballast tanks, while the COW (Chief of the Watch) at the BCP (Ballast Control Panel) immediately closed the ballast tank vents. As a direct result of these timely actions, our dive was killed around 450 feet—our new test depth. We corrected our bubble and began our ascent normally without a steep up-angle. We surfaced uneventfully. But it was a close call, no doubt.

After this unexpected episode of high drama, our Captain then came back over the 1 MC and said that Ensign Smith was going to try the full-on-four dive again. We weren’t exactly reassured by this news, but on his second attempt, the DOOW on instruction pulled it off with no extra excitement.

* * *

Topside Log Mosquito War

We were tied up at port in Charleston, and Bob was standing what we called the mid-watch, which ran from midnight to 0400. We were not at our usual berthing of Pier November; for some reason we were moored at a remote pier further up the Cooper River. It was one of those hot and humid summer nights that South Carolina is famous for.

After finishing his midrats, the shipmate we knew as “Cool Bob” headed topside just before the witching hour to begin the mid-watch. Cool Bob surveyed his kingdom and saw nothing out of the ordinary, in fact he saw almost nothing period. It didn’t look like the commies were going to attack the Trumpetfish that peaceful night, with nothing but the sound of insects to keep him company outside. Still, that didn’t stop the inevitable feeling of boredom from sinking in. In Cool Bob’s case, that occurred shortly into his watch around 0015.

It was then that the first large mosquito started buzzing around his head. Then the pesky things started working on his hide, biting him mercilessly and raising welts. Cool Bob wasn’t going to let this “attack” pass without making an official entry into the topside watch log:

0032: Mosquito problem heavy tonight.

Okay, fascinating to know, but Cool Bob couldn’t leave it at that. No, he decided to fill his time by making “a few” more entries into the log about his one-man war with the insects. By “a few”, I mean that he filled up more than 2 ½ pages of the log with more entries. Here is a sampling:

0056: Large mosquito, bearing 283, 3 o’clock high.

0114: Broadside hit.

0146: Second wave Squadron Delta incoming.

0221: Man Battle Stations Mosquito.

0247: Casualty taken.

0332: Direct hit to sail.

This narration went on for the whole 4-hour watch.

The next morning while Cool Bob was eating breakfast in the after battery room, the below-decks watch informed him that he was to report to the XO’s stateroom ASAP. As anyone with submarine experience will know, that usually doesn’t end very well. The XO doesn’t call you in to tell you how great you’re doing. He is the chief disciplinarian on the boat.

Cool Bob finished his chow and walked to the XO’s stateroom. The door was open, and the XO waved him inside. Upon sitting down, Cool Bob was handed the topside watch log. “Are these your entries?” Of course, the XO already knew the answer. After Cool Bob acknowledged that, yes, those were my entries, the XO lit into him and chewed his butt out for about a half-hour. “Do you realize that this is a part of the ship’s OFFICIAL log? Are you aware that your dumbass entries are there for the world to see? How is this going to look, and how is it going to reflect on the officers and crew?” And so on.

Cool Bob probably felt slightly less cool after that lambasting. He got up to leave the XO’s office with a full understanding of the solemn responsibilities of Topside Watch. He also had to contemplate another order by the XO, that is, that he remove his head from a particular orifice. But not all was lost.

As he was walking out the door, the XO dropped the intimidating tone and admitted, “It was funny… STUPID, but funny.”

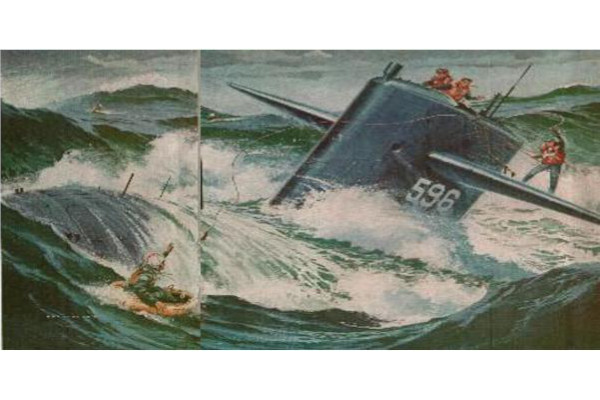

Rescue at Sea – a Hair Raising Story of Bravery and Resourcefulness

From “Sub Tales”

If you ask veteran submariners, to a man they will describe two vastly different worlds: surfaced and submerged. While the distinction is not immediately apparent to those of us who have only read about submarines, those who have ridden and served on them will become quite animated in describing the striking differences between the two environments. On the surface, a submarine is subject to the whims of Mother Nature. In calm waters, the effects are minimal. But where strong winds and massive waves create a maelstrom on the ocean surface, a submarine becomes extremely vulnerable. One such notable example is the North Sea.

… As fate would have it, the OOD of the Scamp was preparing to order the ascent to PD. Despite the terrible weather conditions, it was the usual time for the Scamp to check in with command and receive new orders and other communications. Typically, the Scamp made radio contact during each watch period, which was every six hours at that time. As the Scamp approached PD just before 1100, the aquatic environment quickly changed from calm to chaotic. Sonar indicated no surface traffic nearby, but a quick scan of the surroundings by the observation scope revealed a very angry sea. The radio mast was extended under some duress, as the Scamp pitched and rolled violently. The radio operator received the transmissions and immediately called CO Duma in Control. An urgent message had been issued to the Scamp:

Contact SUBLANT watch officer concerning distress vessel vicinity 35-58N 052-57W ASAP.

The message from SUBLANT (Submarine Force Atlantic) in Norfolk was brief but contained the estimated coordinates of the endangered ship.

No other boats were close to the stricken Balsa 24. Although the fast-attack submarine was certainly not designed for surface rescue operations, the command was clear: Lives were at stake, time was at a premium, and if any water rescue was going to happen, it would be up to the crew of the USS Scamp. CO Duma took the Conn and ordered the Scamp to dive to a safer depth. He got on the 1MC and announced the change of plans to the crew. In so many words, he told them that their homecoming was going to be delayed. Some Filipino sailors were adrift on a raft on the raging seas near their foundered ship, and any chance for survival would require the willingness of the crew of the Scamp to risk life and limb to attempt a surface rescue.

… Here’s the first-hand account of that initial encounter with the Balsa 24 from Charlie Grandin, a Third Class Petty Officer standing watch as a quartermaster (QM):

At around 1100 on the 24th of February 1987 while transiting back to our home port of Groton we received a vessel in distress message from SUBLANT. The Balsa 24 was taking on water in a massive North Atlantic storm due to the clay they were hauling, which clogged their bilge pumps. We were the closest in the vicinity and we proceeded at best speed to the provided Lat/Lon.

We arrived on the scene about 1500 and surfaced IVO Balsa 24. It was foundering and sinking. It was extremely difficult rigging the bridge due to the beating the submarine was taking on the surface (extreme rocking and rolling). Opening the sail clamshell, I simply could not believe the enormity of the seas. In my 30-year career, I don’t recall any weather like the North Atlantic that February evening.

… Fully cognizant of the difficulty of the task ahead, Duma called down to the rescue party mustered in Control. “Rescue party topside!” One at a time, the five men ascended the ladder with rescue lines in tow. Everyone but CPO Conway squeezed into the bridge, a space normally occupied by two or three men. Conway continued forward to a second ladder inside the sail that led down to a door opening at the deck level. He gathered himself for the bracing wind and rain that would greet him upon exiting the sail; first, though, he secured his tether line to a steel pipe. That turned out to be a smart move. When he opened the door, a huge wave swept over the deck and knocked him over, snapping his safety line before he had even emerged from the sail. The notion of swimming over to the nearby raft would be a suicide mission.

… Charlie Grandin remembers the physical challenges of trying to discharge his duties as QM that afternoon and evening inside the uneasy confines of the Control Room, as the Scamp succumbed to the pounding of the restless Atlantic Ocean:

I remember holding onto/hanging from/dangling from the Navigation Plot due to the large, violent and heavy rolls… The Sea State was at least a 6 (reported) and the Wind Scale was 7+. We continued rescue attempts until the dusk light was too dim (around 1900). The heavy winds were blowing and tumbling the life raft around like a small toy. With night upon us, we buttoned up the sail and shut the hatch for the evening. All night long we stayed surfaced, rigged for red, getting continually slammed around by the seas. The helmsman and planesman working alongside me in Control had large plastic bags tied to the armrests of their chairs to vomit in, while I plotted bearings to the beacon. It was surreal.

(This is only a small sample of the entire rescue story. There are many pictures in the book that illustrate the danger.)

Extreme Danger Lurking at Periscope Depth in the Med

From “Poopie Suits & Cowboy Boots”

Before I detail our role in the NR-1 mission, let me describe the unusual ocean conditions encountered in the Med. The water temperature profile of certain portions of the Mediterranean Sea is unique; in some areas, the same water temperature on the surface extends down 80 to 100 feet. This unusual phenomenon, called an isothermal, can prove advantageous in detecting ships at long range on the surface, where the same temperature prevails for many miles away; in fact, this was where we detected a Soviet vessel about 250 miles away, as I described in Chapter 11.

While sonic detection is enhanced horizontally in these conditions, the vertical detection of sound is greatly degraded. Herein lay the accompanying disadvantage of these isothermals for our sonar capability aboard the Seahorse. If we were at the surface or say, periscope depth of 60 feet, our sonar reflected off the water below us at the temperature gradient. The colder waters at 80-100 feet or deeper served as a sonic mirror that prevented us from properly clearing baffles, as we couldn’t exclude an enemy vessel immediately below our hull. The same problem occurred in reverse as well, meaning that if the sub were below 100 feet, it might not be able to detect a shallower vessel nearby. This acoustic blind spot created that nagging feeling that we might not be aware of all possible obstructions in our surroundings. One day in the Med we nearly found out the hard way that our intuition was correct in this regard.

On that morning, we had been submerged fairly deep, and the captain decided to surface. First, we came up to 100 feet and cleared baffles. The Sonar Shack didn’t hear anything, so we proceeded up to periscope depth to take a quick 360-degree look at the surface, per usual routine, before continuing to surface. I was the DOOW that day, and Mike, the JO who had masterminded the Penn State prank on Dave earlier in the year, was training on the #1 periscope in the Conn. After the scope broke the surface of the water, Mike started to swivel the periscope to complete his survey.

About halfway on his rotation, Mike suddenly lifted his head from the periscope and froze. His jaw dropped and his gaze widened. The captain, who had been seated in his customary chair at the rear of Conn, leaped up and shoved Mike out of the way. He peered into the periscope, and what he saw shocked him. It was a huge Japanese fishing trawler, and it was heading straight toward the submarine. These floating fish factories were commonplace in the Med; the crew cast massive nets to ensnare the fish, and the catch was processed, frozen and packaged right there on board before finding its way back to the consumers of Japan. The draft (the vertical distance between the waterline and the bottom of a ship’s keel) of this enormous vessel was deep enough to collide with our sub if we didn’t immediately act.

The Japanese boat was no farther than 100 yards dead ahead and approaching us fast. This emergency was what we called a “5 by 5”, meaning that the vessel as viewed within the periscope was so close that it occupied all five reticles on the eyepiece both vertically and horizontally. The captain acted quickly. He slammed the periscope handles, and the scope began to lower. “Emergency deep! Emergency deep!”, he shouted. As the DOOW at the time, it was my job to give the proper sequence of commands to the helmsmen before me. “All ahead flank!” The helmsman replied, “All ahead flank aye.” Then I immediately barked, “Twenty-degree down angle!” “Twenty-degree down angle aye!” came the reply. The sub began to quickly dive, and we braced for either impact or near-collision.

As we dropped quickly in the water, we could hear the unmistakable swish swish swish of the four propellers of the fishing trawler growing louder and louder. It was a rhythmic sound that sent fear into all of us in Control. Thank God, the trawler passed directly overhead, perhaps 20 feet away. We escaped intact, but it was one of the most frightening moments of my submarine service. It also highlighted the critical importance of gaining muscle memory for urgent situations that must be dealt with swiftly and accurately to avoid calamity aboard a submarine.

All of that initial practice at Idaho Falls and Groton, followed by the months of training ops in the Charleston basin aboard the Seahorse, had paid off in a big way, and I had been able to calmly discharge my duties without hesitation. The same was true of everyone else on board during that close call. Although this incident was rather dramatic, the same psychological tension persisted at a steady background level whenever we were at sea because you never knew when the next emergency would occur. The only thing you did know with certainty was that there would always be a next emergency. I’ve heard other sub vets shrewdly put it this way: Life aboard a submarine was 99% routine and 1% terror. There wasn’t much of an in-between.

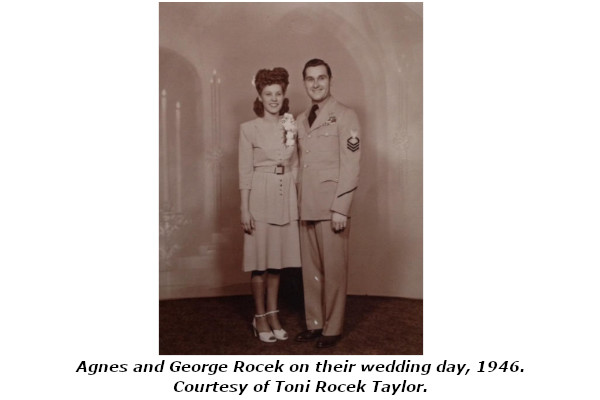

The Unbelievable Story of George Rocek, and the Will to Survive

From “Sub Tales”

On 18 November, the Sculpin encountered a Japanese convoy in her patrol zone and began to give chase. The story of the ensuing battle is a compelling story of its own and described in better detail elsewhere, but here’s the nutshell version: the following day after more than nine hours of blasting during sustained back-and-forth combat, the Sculpin sustained a fatal shelling by the Japanese destroyer that was relentlessly pursuing her—the Yamagumo. The commanding officer of the Sculpin, Fred Connaway, was instantly killed when a blast directly struck the conning tower. As general chaos ensued with the extensive carnage and mechanical damage, senior officer Cromwell and 11 other men made a fateful decision to go down with the submarine. Cromwell had possession of privileged intelligence regarding enemy submarine movements and attack plans—information that he knew the Japanese would try to extract by any means necessary—so rather than risk further harm, he intentionally took those classified secrets to his watery grave. The story was not learned until after the war, and Cromwell’s heroism was rewarded posthumously by the Congressional Medal of Honor.

While Cromwell and a handful of crew members had chosen to go down with the ship, the Yamagumo caught George Rocek and the remaining sailors on board in a deadly barrage. As an enlisted man, Rocek had no privileged information to protect; rather, he and his besieged crewmates were fighting for their very survival. The order had been given to Abandon Ship, and the submarine was rapidly losing freeboard. Sinking was imminent. Here’s Rocek in his own words:

On reaching topside, I saw one man bloody and dead. I started running for the sail and looked to see where the ‘can’ was—which was on my side. I started through the doghouse (author’s note—a hidden compartment at the base of the sail) to the port side when a direct hit was made. I was momentarily stunned and numb all over. After seeing that I was intact, I jumped over the side. Once in the water, I watched the Sculpin submerge in a normal manner. Pete Gabrunas was manning the hydraulic manifold, and on scuttling the boat, he and others were unable to escape due to the wreckage in the Conn. I could feel explosions, apparently from the batteries.

George nearly didn’t live long enough to witness the sinking of his beloved submarine. As soon as he had jumped overboard, the violent ocean forces around the boat seemed to pull him further and further below the surface against his will. He felt powerless as he struggled to turn back to the surface. George later recalled that at that moment, his entire life flashed before him like a movie as he contemplated his imminent demise. But then, as if by divine providence, his underwater path collided with a large air bubble that swept him up and delivered him nearly effortlessly back to the surface. It would be the first of many improbable twists and turns of fate for George Rocek.

George had just enough stamina to swim to a floating piece of debris. While he regained his breath, he and the others who had been forced to flee the Sculpin watched with disbelief as the crippled boat prepared for Eternal Patrol. Those who witnessed the Sculpin’s last moments on the surface recalled how gracefully her sail turned down beneath the waves for the final time. Moments later, a loud boom from below sent up a giant geyser of seawater into the sky—the explosion of the ship’s batteries signaling her demise. Meanwhile, Rocek and dozens of his shipmates clung to jetsam in the oil-choked sea, checking their flesh for the countless shrapnel wounds that the shelling had inflicted. The Yamagumo hauled survivors aboard who could help pull themselves up on the rescue lines; one severely wounded sailor was thrown back into the water after his injuries were deemed too serious to survive.

George Rocek began that morning aboard his familiar submarine and ended the day on the deck of an enemy destroyer, along with 40 of his shipmates. The Japanese bound and blindfolded all of their new prisoners. The captured Americans were forced to sit in a very tight formation on the open deck. Many of them lost large amounts of blood from their gaping shrapnel wounds. Rocek recalled that although he couldn’t see what was happening, he could hear the painful moans of his injured crewmates and feel the sting of rain on his body during a very heavy thundershower that night. The hellish experience had only begun.

At some point several days later, the Yamagumo arrived at the island of Truk (one of the thousands of islands of modern-day Micronesia). There, the debarkation of the American prisoners occurred with a heavy dose of brutality. Rocek later recalled that the Japanese escorts beat any American captive suspected of trying to peek through his blindfold as the haggard group was led in single file to a building near the harbor. For nearly two weeks, the 41 American survivors existed in three 8 x 7-foot windowless cells, each with a hole in the floor serving as a primitive latrine.

The only reprieve that the darkened prisons offered was the removal of the blindfolds while inside. Food and water were initially withheld as each man was systematically interrogated and, in many cases, beaten and tortured. Rocek would only say that many of them took “some hard beatings”. During these intense periods of questioning, failure to answer immediately resulted in forceful blows with a large wooden plank. The pain of these encounters was exacerbated by the inability of the Japanese interrogators to speak intelligible English, such that a beating was nearly guaranteed during every grilling. Here’s George Rocek in his own words:

We were let out of our cells twice a day for about 10 minutes, an event to which we gratefully looked forward to. Repeatedly, we were taken out of the compound for questioning—always blindfolded. If you hesitated in answering a question, you received a whack across the rear with a piece of wood larger than a bat. I learned to bide for time by saying I didn’t understand the question.

About the tenth day, they shaved all our hair off and issued us Japanese Navy undress blues to wear, and a square, flat, wooden block with Japanese writing on it to wear around our necks. Three of our wounded men returned from the hospital. One man had his hand amputated and the other, his arm. They told us that the amputations were done without any anesthetic, and they were questioned at the same time.

When sustenance was eventually offered, it consisted of just one small ball of salty rice and a few ounces of water daily. No first aid was rendered for the men’s copious wounds upon arrival, and many of the injuries became infected. To stave off complications from their wounds, the injured American sailors used their urine as an antiseptic wash. Only when a man’s wounds started oozing foul-smelling pus was a visit to the infirmary arranged. The interrogations and beatings continued like clockwork at a relentless pace. The time spent on Truk was a grueling and spirit-breaking experience by all accounts. Rocek couldn’t imagine that conditions could worsen, but they did.

After 12 days of subsistence in their cramped cells, the POWs were rounded up with blindfolds in place and put into two nearly equal groups. Rocek’s group had 21 men, and the other group had 20. The men were put in trucks and driven down to the shoreline, where each group boarded separate Japanese aircraft carriers. While one group was put on the carrier Unyo, Rocek and his band of brothers stepped aboard the Chuyo, where they were escorted below deck to a small holding compartment. This room was locked and guarded; all 21 men were squeezed inside like sardines in a can.

What happened next is proof-positive that truth is stranger than fiction. To comprehend the incredible coincidence that took place, we must suspend the narrative briefly and step back in time to 1939 along the New England coastline. It was then that the USS Squalus (SS-192) went down in 240 feet of water near Portsmouth, New Hampshire. One of the boats that came to her rescue that day in May was her sister ship of the Sargo class: the USS Sculpin, the same submarine that would go down in the Pacific four years later. After the successful rescue of her crew using Swede Momsen’s revolutionary submarine bell, the Squalus was raised from the ocean floor, repaired and recommissioned the following year. (See the accompanying story elsewhere in this book detailing the heroics of the Squalus rescue.) The salvaged submarine maintained the same hull number (SS-192) but was rechristened as the USS Sailfish on 09 February 1940.

Believe it or not, the Sailfish—the rechristened Squalus—was conducting her tenth war patrol in the Western Pacific in late December 1943 when she made radar contact with an enemy escort aircraft carrier—the Chuyo. Of course, at the time that pursuit was initiated, the Sailfish had no way of knowing that its Japanese prey was carrying 21 American POWs. Now, stop a moment to ponder the intertwined fates of the Sculpin and the Squalus/Sailfish. Four years earlier and a half-planet away, the Sculpin had been instrumental in the retrieval of the stricken crew of the Squalus. The Squalus, pulled from the ocean floor and given a second lease on life as the Sailfish, was now pursuing an enemy ship carrying half of the survivors of the sinking of the Sculpin. This unlikely twist of fate would prove to have lethal consequences.

This unbelievable story continues in the book, with many more pictures.

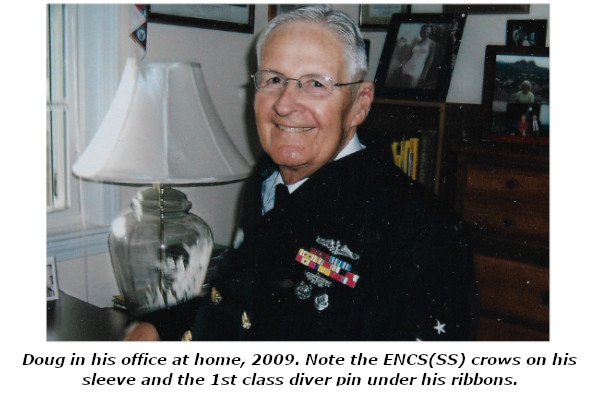

WWII Veteran Doug Bryant Tells What’s it Like to be Depth Charged

From “The Silent Service Remembers – Vol II”

FH: Doug, tell us about your first war patrol during World War II.

DB: We left Pearl on 13 September 1944. I was a motor machinist’s mate (MoMM). We stopped at Midway to refuel a few days later, and two weeks after we had left Hawaii, we entered our first war patrol zone near Nansei Shoto (Ryukyu Islands) in the East China Sea. We scored our first hit, an armed Japanese trawler, on October 10th.

FH: What happened next?

DB: On October 28th, we sighted our first convoy. It was zigzagging every five minutes or so and moving at about nine knots. We moved ahead of it on the port side and fired at two cargo ships, then lost depth control and dropped to 85 feet. A couple of minutes later, we heard three loud explosions. The convoy’s escorts had started dropping depth charges. We stayed submerged and could hear the sounds of ships breaking apart. A few minutes later we heard a loud explosion. We later learned that we had sunk a Japanese collier and a gunboat.

FH: I have read that the Sea Dog was the target of more than 100 depth charges that morning, dropped from both Japanese ship escorts and aircraft. What was your first impression of being depth-charged?

DB: I guess I was so young, and I had heard all of the sea stories from the older sailors about how bad it was, that when we took the first couple of depth charges, I didn’t even think that they were that close. But later on during the war, as we took on more and more depth charges, and we passed through mine fields, and especially when we were accidentally bombed by our own planes, it got pretty scary.

FH: You made five war patrols on Sea Dog during World War II. Tell us how you coped during the depth charge attacks.

DB: Sitting in the Engine Room during a depth-charge attack, we could hear the destroyer approaching above us and dropping the depth charges, one by one. The sound of each depth charge would get louder and louder as the bomb got closer and closer. We could tell from which side of the boat the sound was approaching, and all eyes on board would be facing in that direction, watching and waiting. Then, a few seconds later, the sound would be on the other side of the boat, signaling a miss. Everyone would breathe a sigh of relief because they had missed us, at least that time.

FH: What was the strategy to avoid getting hit?

DB: I think the big thing that saved us was that we were actually at a greater depth than the Japanese thought we were. I guess they figured we couldn’t go down that far, so they were setting their depth charges to explode above us. The only real damage we took was from friendly fire. We took five bombs from our own planes…I remember big chunks of cork being blown off the bulkheads, lights breaking and going out, and completely losing power. Scary stuff, but it wasn’t until after the war that we all realized just how lethal the Japanese depth charge campaign had been. We were lucky. Other American boats weren’t so fortunate.

FH: What was the longest time that you were forced to remain submerged during depth charging?

DB: We were down more than 24 hours during one attack. We just could not get away from them, and they followed us and dropped more than 40 depth charges over that period of time. The air inside the boat was getting bad, and we had put down the carbon dioxide absorbent and bleed fresh oxygen into the submarine. But the smoking lamp never went out! It only went out when we went to Battle Stations, but otherwise there was no time that we couldn’t smoke.

On a normal day in the Pacific during a war patrol, we dove around 0430 and remained submerged until at least 2000 that evening. The air quality got worse as the day went on. You could tell because you would start panting if you tried to do any heavy work. You just couldn’t get enough oxygen in your lungs. Plus, the air pressure inside the hull would be building up from the added oxygen. But no one seemed to mind.

We all looked forward to coming back to the surface at night. We’d run the low-pressure blower to reduce the inside pressure before we opened the bridge access hatch. But once that hatch was open and fresh air started pouring into the boat, you felt like a new man. During those times, few men were allowed to go topside. I was one of the few, because I was a Battle Stations lookout and supposedly had very good eyesight.

FH: You were a participant in Operation Barney in the spring of 1945. This was a highly risky offensive directed by Vice Admiral Lockwood to retaliate for the sinking of the USS Wahoo (SS-238) in 1943. The idea was to sink as much Japanese tonnage in the Sea of Japan, but first the nine US submarines—including the Sea Dog—had to traverse the dangerous Tsushima Strait, which was heavily patrolled and riddled with mines. Your recollections?

DB: Yes, that was a tense affair. By that stage of the war—May/June 1945—there was relatively little Japanese shipping left to sink. At the time, Japan was still trading with Russia; keep in mind that Russia actually didn’t declare war on Japan until August 1945, after the A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and a day before the bombing of Nagasaki. Up until then, Russia was Japan’s major trading partner, so what was left of their merchant shipping was up in the Sea of Japan. That’s where VADM Lockwood wanted us to go.

The only way into the Sea of Japan from the south was through the Tsushima Strait, which as you said was heavily mined. We took on some new equipment that they called “mine-detecting gear”; it was basically nothing more than underwater sonar, which of course was new at the time. So the nine submarines chosen for the operation left Guam; three boats leaving on three successive days.

The Japanese mines were attached by cables to anchors at the bottom of the ocean. The mines were placed at different depths, generally about 30 feet below the surface if I recall, and designed with magnetic triggers to explode on contact with the steel hull of a submarine. I remember on a couple of occasions, we would pick up a mine dead ahead; we would back down and change course. One time, we actually hit the cable of a mine; we were too deep to make contact with the mine itself. Even that could have meant curtains since the boat could drag the cable and force the mine down to make contact. We all knew that, so when we heard the sound of the cable scraping against the hull, we listened as the sound passed from fore to aft and finally disappeared. If that cable had gotten snagged on any part of the superstructure, we would have been goners.

I should note that although nine US subs went into the Sea of Japan, only eight returned. The Bonefish (SS-223) was lost. We were close enough actually to hear her being depth-charged. I remember sitting in the After Torpedo Room, passing the time with a game of Acey-Deucey, and having the game interrupted from time to time by the sound of the Bonefish getting depth-charged behind us. Of course, we were all young men—indestructible—and we were all laughing. “They’re getting their asses knocked over!” By then all of us were very familiar with the depth-charge routine, and I guess it was a coping mechanism. None of us ever considered that one of our boats wouldn’t make it back. So that was very sad when we found out.

FH: What was your most memorable experience from Operation Barney?

DB: We entered the Sea of Japan between Japan and the Korean peninsula as part of the nine-boat wolfpack and proceeded north. Shortly thereafter, we made a nighttime attack on a huge Japanese freighter that was anchored in a harbor on the west coast of Honshu at Niigata. The size of the ship was hard to comprehend; we were so much smaller.

I was the Battle Stations lookout; as I said, I had really good vision especially at night. After we fired our torpedoes, I watched the ship explode in a spectacular ball of fire. It looked like the entire superstructure was heaved high in the air by the initial explosion. The bow broke, and the ship sank. The sound of the hit was deafening, and the intensity of the fireball burned itself deep into my mind. I was so caught up in the moment that in the eerie silence that followed, I finally looked down and realized that my knees were shaking violently. Even today, I can still see it clearly, as if I were there again in person. In fact, I think about it almost every day.

A close second for the most vivid memory of Operation Barney was that scraping sound of a mine cable passing along the entire port length of our boat. Tense times. One other stray fact about that time: Of the eight enemy ships that we sank on the Seadog during the war, six of them were during Operation Barney.